Reducing the execution time for breaking elliptic-curve cryptography using Active Volume and photonic hardware

Researchers from PsiQuantum and the Hartree Centre have published the first physical resource estimate to execute a quantum algorithm for breaking Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) over binary fields.

Key Insights

ECC over binary fields is related to the more widespread ECC over prime fields; ECC over prime fields is used for many encryption tasks, e.g., securing web traffic (the HTTPS in web addresses), the Bitcoin blockchain, messaging applications, etc., while ECC over binary fields is more often used for applications that require a small hardware and power footprint like smart cards, passports, or small low-power Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices

~2000 to ~7500 logical qubits are required for breaking ECC keys of relevant size between 163 to 571 bits in length, respectively; this corresponds to between ~2.5 million and ~11.6 million matter-based qubits (e.g., superconducting circuits) and runtimes between 2.4 minutes and 56.2 minutes on a superconducting-circuit device with a 1 µs code cycle

Using PsiQuantum’s Active-Volume architecture and photonic-based hardware of data-center size, the runtime can be improved by at least an average factor of 2.2x: 1.2 to 23.4 minutes using Active Volume vs. 2.4 to 56.2 minutes using superconducting circuits; this factor can be further improved by increasing the component density of the quantum computer

Quantum computers that are able to execute this algorithm are still some time away; nevertheless, the fact that the encrypted data is vulnerable emphasizes the need for encryption methods resistant to QC

Context setting: Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) over binary fields

Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) is a cryptographical method relying on mathematical properties of elliptic curves. Before diving into the novel research introduced by the PsiQuantum and Hartree Centre researchers, let us first provide a bit of intuition on how to think about these curves and why they are very useful for encryption.

For visualization purposes, elliptic curves can be thought of as contours in the 𝑥−𝑦 plane made up of pairs of points (𝑥,𝑦)

that satisfy a specific equation. The general form of that equation is:

𝑦^2=𝑥^3+𝑎𝑥+𝑏,

with 𝑎,𝑏 parameters that specify a given curve. One widely known example is “secp256k1”, the elliptic curve used to encrypt the Bitcoin blockchain, with 𝑎=0, 𝑏=7. Its form is:

𝑦^2=𝑥^3+7

For practical purposes, 𝑥 and 𝑦 are limited to being smaller than some prime number, so that the field of possible pairs is not infinite, e.g., an elliptic curve secp256k1 defined over the field of 13 includes all (𝑥,𝑦) pairs of integer numbers that satisfy the equation above, and where 𝑥 and 𝑦 are between 0 and 12.

The reason why these curves are useful for cryptography is that they obey special rules for adding (𝑥,𝑦) pairs, i.e., points on the curve: points on the curve are added in such a way so that the resulting point again falls somewhere on the curve. In essence, by adding points, or adding the same point to itself many times, we are “jumping around” the curve, sometimes forward and sometimes backward. After many jumps, the starting and final points do not seem related at all, so figuring out how many jumps occurred becomes an exponentially difficult challenge. This is what gives ECC its power.

When we now consider binary fields, the fundamental intuition does not change much, even though the details change: the (𝑥,𝑦) pairs are now binary numbers, and the equation of the curve is slightly modified to:

𝑦^2+𝑥𝑦=𝑥^3+𝑎𝑥^2+𝑏

Adding points still keeps us on the curve, and it is equally difficult to figure out how many jumps it took from the starting point to the final one; however, operations between binary numbers are easier for classical computer hardware to manage. Therefore, ECC over binary fields is more often used for small and low-power devices such as smart cards, passports, or Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices, while ECC over prime fields is more used for general encryption tasks, such as securing web traffic, messaging applications, or the Bitcoin blockchain.

When compared to RSA encryption, an ECC key requires approximately an order of magnitude fewer bits to provide the same level of security, e.g., the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) recommends using either an RSA key of 3072 bits in length or an ECC key of 283 bits for equivalent security levels. Simultaneously, the shorter key allows quantum computers to require fewer quantum resources to execute a successful attack.

Novel research

This resource estimation is the core of the novel research by colleagues from PsiQuantum and the Hartree Centre: it is the first logical and physical resource estimate for computing ECC keys over binary fields with key lengths between 163 and 571 bits, relevant for ECC implementations in real-life circumstances.

Building on previous work in the field, the authors optimized existing algorithms and added a functionality that is capable of handling special addition cases, e.g., adding a point to its inverse on the curve (same 𝑥, opposite 𝑦), or adding the identity element (point representing zero in regular addition). The outcome is the first quantum algorithm capable of exactly computing any point addition operation, including the special cases mentioned above.

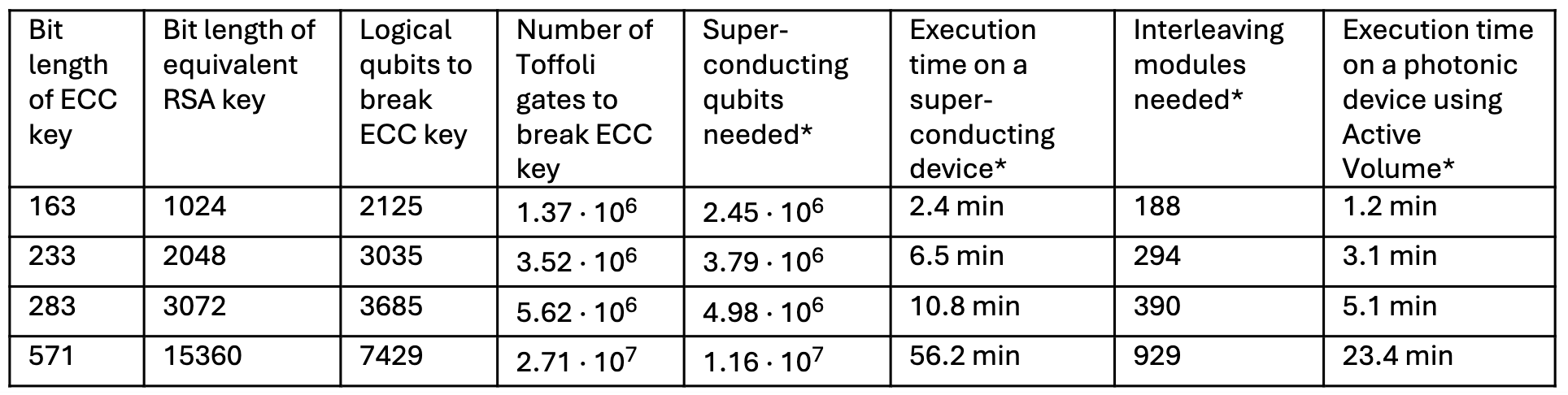

The results for the resource estimates are in the table below:

* The results listed here are excerpts from the full list of results in Tables VI, VII, and VIII from the text of the article representing realistic conditions for comparison between matter-based qubits and PsiQuantum’s photonic devices.

Using PsiQuantum’s Active-Volume architecture and photonic-based hardware, the execution time can be improved by at least an average factor of 2.2: 1.2 to 23.4 minutes using Active Volume vs. 2.4 to 56.2 minutes on a superconducting device using the Baseline architecture. This execution time assumes that the photonic-based quantum computer is the size of a data center and that photon-qubit resource states are generated from physical units called interleaving modules at a rate of 1 GHz. The execution time can be further improved by increasing the density of components in the device, e.g., 10x more interleaving modules in a cabinet accelerates the computation tenfold. Taking a bigger-picture look, whichever quantum computer of sufficient size is used, it takes less than an hour to break even the most secure ECC key, which has implications for cybersecurity.

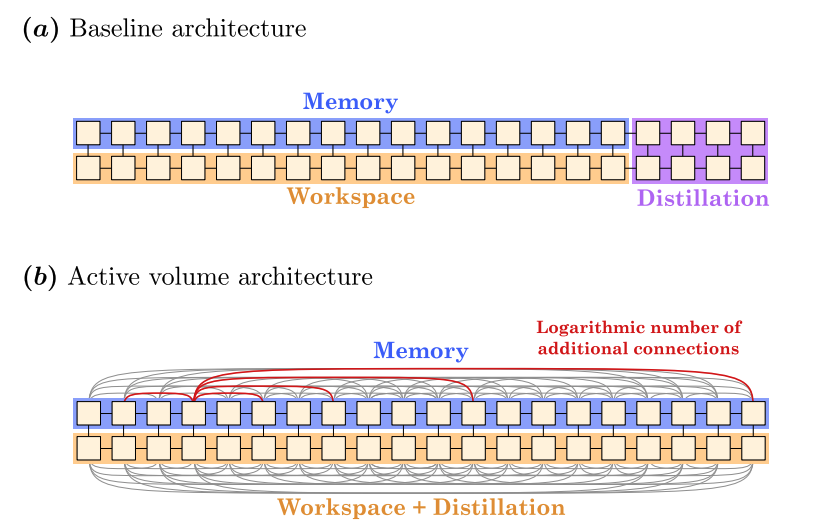

Figure 1: Active Volume Architecture

Schematic representation of the difference between the Baseline architecture and the Active Volume architecture for logical qubits (yellow squares). (a) The Baseline architecture is a 2D architecture in which logical qubits are connected to their nearest neighbors. It is split into three sections: (i) the Memory section stores the information that is used in the quantum algorithm, (ii) the Workspace section is used to connect the different logical qubits from the Memory section when operations are required between them, and (iii) the Distillation section produces the magic T states required for quantum operations via magic-state distillation. (b) The Active Volume architecture introduces additional connections between logical qubits. Additionally, the Distillation section is absorbed into the Workspace section to increase the utilization of the logical qubits. Here, the additional connections for the 4th logical qubit from the left in the Memory section are represented.

Cybersecurity implications

With logical qubit counts above 2000 for the smallest key length, and no existing quantum computers in the world able to execute the quantum algorithm, there is no immediate risk to encrypted information. However, it is a matter of “when”, not “if”: eventually, there will be a quantum computer capable of breaking ECC and RSA encryption.

This is why encryption that is resistant to quantum-computing attacks, also called post-quantum cryptography (PQC), is needed. NIST has published a set of protocols after a lengthy evaluation process, and organizations are encouraged to start transitioning their encryption protocols as soon as possible, with a recommended target of 2030 for a full transition away from RSA and ECC encryption. While five years may sound far away, there exists such data that is encrypted now and that will still be valuable to keep secret in five years, so an early start is warmly recommended to reduce the risks of harvest-now-decrypt-later attacks.

What’s next?

For researchers, there is still some headroom for optimizations of the quantum algorithm, e.g., by diving deeper into the subroutines of the algorithm and optimizing their Active Volume resource requirements, parallelizing some operations when running the algorithm multiple times, or tuning the ratio between qubits dedicated to memory and computation. These improvements would further reduce the execution time, making it possible to run more instances of the algorithm once a sufficiently large quantum computer exists.

For organizations and governments, the next step is transitioning encryption methods to PQC, so that information intended to stay secret is not jeopardized by any quantum computer in the future.

Essential Terms

Key length: size of the number in bits that is used to encrypt a piece of information. E.g., a 2048-bit key, used for RSA, is a number encoded in a string of 1s and 0s that is 2048 binary digits long; in a decimal representation that number is between 0 and 22048 – 1, and it can be a very large number with more than 600 digits in length

Interleaving modules: modular continuous sources of photonic qubits, which makes them the building blocks of a photonic quantum computer. They are housed in cabinets and linked with optical fibers in a quantum data center.

Quantum resources: the number of qubits and the number of operations required for a quantum algorithm to be executed; the goal of research is to reduce these as much as possible to enable the execution of the quantum algorithm on smaller quantum hardware that is available earlier